Another World

정영주展 / JOUNGYOUNGJU / 鄭英胄 / painting

2022_0727 ▶ 2022_0821 / 월요일 휴관

별도의 초대일시가 없습니다.

관람시간 / 10:00am~06:00pm / 월요일 휴관

학고재 본관

Hakgojae Gallery, Space 1

서울 종로구 삼청로 50Tel. +82.(0)2.720.1524~6

www.hakgojae.com@hakgojaegallerywww.facebook.com/hakgojaegallery

학고재 오룸Hakgojae OROOMonline.hakgojae.com

1. 범용(凡庸)의 세계(banal world) 속에 존재하는 또 다른 차원 ● 시인 노발리스(Novalis, 1772-1801)는 "철학은 본래 향수이며, 어디에서나 고향을 만들려는 충동이다."라고1) 말한 적이 있다. 예술 역시 향수에 대한 충동에서 태어난다. 고향만큼 인간에게 풍부한 사유를 제공하는 대상도 흔치 않다. 고향은 근원이기 때문이다. 우리가 흙에서 태어나 흙으로 돌아가듯이, 인간의 사유와 인생은 고향에서 출발해서 고향으로 돌아가는 과정에서 펼쳐지곤 한다. 우리에게는 고향으로 돌아가려는 의지가 분명히 있다. 반대로 고향을 어쩔 수 없이 떠나야 하는 처지에서, 고향을 포기해야만 하는 선택의 갈림길에 서게 되는 인간형도 있다. 전자의 모델을 우리는 호메로스(Hómēros, 928B.C.-?)의 오디세우스에서 찾을 수 있다. 후자의 모델은 「성서」에서 등장하는 아브라함(Abraham)이다. ● 오디세우스는 트로이 전쟁이 끝난 후 고향 이티카로 돌아가려 한다. 그 과정에서 영원한 삶과 재물, 권력을 주겠다는 칼립소의 유혹, 인간을 통째로 먹어 치우는 괴물 폴리펨의 위협, 로토스라는 환각제, 사람들이 돼지로 바뀌는 키르케의 섬, 아름다운 노래가 취하게 만드는 세이렌 섬 등의 모든 환란을 극복하고 고향으로 돌아가 부인을 구출하고 가정을 다시 꾸리게 된다. 반면에 아브라함은 신의 명령을 따라서 고향과 가족들, 친구들을 떠났다. 고향은 자신을 지켜주는 공동체이다. 나를 포근하게 감싸주는 이불이다. 익숙하며 편하다. 그러나 아브라함은 신의 명령을 따른다. 안전하지 못한 곳을 향해 모든 것을 버리고 떠난다는 것은 신을 완전히 신뢰한다는 뜻이지만, 동시에 모든 결과를 스스로 책임진다는 뜻이기도 하다. 이것이 아브라함의 고독이다. 고향을 떠난다는 것은 찢어지는 것과 같은 고통을 수반한다. 고향이라는 개념 자체에 인정(人情)과 베풂, 나눔, 공감 등 토대적 정서가 내포되어 있기 때문이다. ● 나아가 신은 아브라함에게 외동아들 이삭(Isaac)을 희생시키라고 명령했을 때, 아브라함의 자아는 절대적 고독에서 존재의 밑바닥까지 추락하여 절대적 죽음을 맞이하게 된다. 자아의 이 절대적 죽음의 경험은 절대적 무(absolute nothing)를 확인한 순간이다. 역설적이게도 영원한 삶은 절대적 무의 확인으로부터 비롯된다. 자아가 없다는 것을 아는 것이야말로 공(空, emptiness)의 진정한 의미이다. 그런데 역설적이게도 공(空)으로부터 오히려 가득 참(fullness)이 현현된다. 나와 모든 사물이 비교와 가치판단의 득실로부터 초월되기 때문이다. 이때 나와 세계는 하나가 되며, 그렇기 때문에 충만 속에 침잠될 수 있다.

정영주(鄭英胄, 1970-) 작가의 세계는 절대적 고독에서 절대적 무를 체험하면서 발현되었다. 작가의 세계는 절대적 무에서 가득 찬 충만을 완성했다는 면에서 아브라함의 역설과 비슷하며, 고향을 떠나서 고향의 고귀한 의미를 얻고 회귀했다는 면에서 오디세우스의 여정을 닮았다. 따라서 우리는 정영주 작가의 작품에서 아브라함의 고독을 발견하게 되며, 동시에 오디세우스의 용기와 마주하게 된다. ● 정영주 작가는 1970년 서울에서 태어나 유년기를 부산에서 보냈다. 다시 서울로 올라왔고 홍익대학교에서 서양화를 전공한 후 프랑스로 떠났다. 베르사유(Versailles)에서 수학했다. 프랑스에서 작품을 인정받았으며 작가생활은 안정되었지만, 1997년 뉴욕으로 이주해 새로운 환경에서 작가생활을 시작했다. 국제화단의 생기를 주도하는 본거지에서 인정받고 싶다는 오랜 숙원을 이루기 위해서였다. 그러나 작가로서 미처 자리 잡지 못한 시점에서 불운이 거듭되었다. 1998년 작가의 개인적 현실은 국가적 환란을 비껴가지 못했다. 당시 작가가 천착했던 구성주의적 추상회화도 아직 완결점에 이르지 못했던 시절이었다. 곡절로 점철된 여정을 마무리하며 귀국할 수밖에 없었다. 그러나 귀국은 진정한 귀향이 아니다. 아브라함의 절대적 죽음을 아직 맞이하지 않았거니와 오디세우스가 실현했던 페넬로페의 구출은 이루어지지 않았기 때문이다. 정영주 작가는 구성주의 회화, 추상표현주의, 숭고주의 계열의 회화를 두루 섭렵했지만, 그것은 진정한 자기가 아니었기 때문이다. 예술가에게 진정한 자기를 찾는 것이야말로 가장 중요한 사건이 아닐 수 없다. 오디세우스에게 페넬로페의 구출이 지상의 과제였던 것처럼, 예술가에게 자기만의 회화형식과 이야기를 찾는 것이 절대적 목표가 된다. 이 목표를 성취한 작가는 매우 드물다. 그리고 예술가는 자기정체성(self-identification)의 확립에서 존재 이유와 근원적 생명을 담보할 수 있다. ● 자기정체성은 아이러니하게도 위기(crisis)로부터 찾아온다. 위기는 나를 극단으로 내몰며, 극단 속에서 나는 타자와 구별되기 때문이다. 위기(crisis), 구별(discrimination), 비판(criticism), 기준(criterion), 죄과(罪過, crimen)는 모두 한 뿌리에서 비롯된다. 이 단어들은 모두 구분 짓는다(to differentiate)는 뜻을 지니고 있다. 정영주 작가는 2000년대 초반 모든 것이 무너지는 경험을 했다고 한다. 그림은 뜻대로 되지 않았으며, 운신할 수 있는 돈마저 없었다. 지인은 하나둘 떠나갔으며, 남은 것은 힘없는 시선 하나밖에 없었다. 작가는 이때 스스로 물었다. "살아서 뭐하나?" ● 살아서 무엇 하겠느냐는 절박한 질문 속에서 실존의 의미가 펼쳐진다. 이때 나는 범용한 사람과 구분된다. 자기비판(self-criticism)은 "나는 누구인가?"라는 본질적 질문으로 승격된다. "나는 누구인가?"라는 질문에 대답하기 위해서 나는 모든 기준(criteria)을 찾아 헤매다 돌이킬 수 없는 치명적 실수를 범하게 된다. 어떠한 기준에 자기를 투사해도 대답은 나올 수 없기 때문이다. 급기야 나 이외의 모든 타자를 비난하게 되며, 나는 타자로부터 완전히 분리된다. 범용한 세계(a banal world)에서 이러한 행위와 질문의 과정은 죄과(crimen)에 해당한다. 그러나 또 다른 차원(another world), 즉 예술세계(art world)에서 이러한 행위와 질문은 죄과가 아니라 반대로 신화(myth)가 된다. ● 정영주 작가는, 세상이 무너진 것만 같았던 심정 속에서 보내던 어느 날, 도심을 배회하다 거대한 고층건물들 속에 에워싸여 있는 몇 개의 조그맣고 퇴락한 집들을 발견했다. 낡은 슬레이트와 금방이라도 주저앉을 것 같은 기와지붕에 부식된 대문, 금 간 벽이며 침울하게 가라앉는 듯이 하는 축대와 이끼 낀 지반이 작가의 시야에 들어왔다. 화려한 빌딩과 대조되어 더욱 초라하게 보이는 집들이 작가 자신과 동일시되었다. 유년기에 부산에서 익숙하게 보았던 풍경이기도 했다. 작가는 "너희들은 어찌 그렇게도 나 같은 거니?"라며 몇 번이고 되뇌었다. 2008년 무렵이었다. 그리고 「도시풍경」 연작을 그렸다. 위용 있게 상승하는 수직적 이미지의 고층건물과는 대조적으로 수평으로 서로를 기대며 겨우 버티고 있는 집들의 그림이다. 위용 있는 빌딩에 두드러지게 활약하는 사람들의 활력의 의미를 불어넣었고, 초라한 집에는 작가 자신의 처지를 비유했다. 동시에 전자에 미술사에서 빛나는 작품들의 이야기를 위탁했고, 후자 속에서 자신이 가야 할 예술의 기미(機微)를 예견했다. 그리고 시간이 지날수록 빌딩을 서서히 삭제해서 갔고 퇴락해가는 집들로 가득 찬, 너무 새로워서 종전에는 볼 수 없었던, 이계(異界)로서의 풍경회화의 세계를 개진했다. ● 예술의 길은, 그리고 인간의 사유와 인생은 고향에서 출발해서 고향으로 돌아가는 과정에서 펼쳐지곤 한다. 정영주 작가는 고향에 대한 두 가지 모델 중에 아브라함의 모델을 택하며 고향을 떠났다. 프랑스에서 서구 사조와 사상을 익혔다. 그리고 쉽게 갈 수 있는 곳을 에돌아서 한발씩 겨우 내디디며 어렵게 고향에 돌아왔다. 고향은 결론을 말해주었다. 자신의 근원을 속이면서 얻는 것은 허무할 뿐이라는 사실을 이야기해주었다. 작가는 생각했다. "내게 가장 익숙한 그것이 진리이리라." ● 작가에게 아브라함의 신은 서구의 미술 사조와 사상이었다. 이제 그 신에 대한 책임을 스스로 떠안으며 용기를 내어 신에게 작별을 고했다. 그 대신 오디세우스가 그랬던 것처럼 가족과 고국으로 돌아왔다. 칼립소가 오디세우스에게 약속했던 것은 재물과 영원한 삶이었다. 작가에게 빗대자면 명성일 것이다. 오디세우스가 칼립소의 약속을 거절했던 것처럼 정영주 작가도 이를 물리쳤다. 사람을 잡아먹는 폴리펨은 야만의 시대를 상징한다. 정영주 작가는 야만의 시대를 경험했고 지극히 어렵게 극복했다. 국가의 환란과 언어장벽, 정보 불균형, 후기자본주의의 경쟁주의, 글로벌리즘, 병든 철학의 치세(治世)라는 야만을 모두 겪고 극복했다. 로토파고스 섬의 환각제는 가상 세계에 빠진 인간의 모습을 상징하는 것 같았다. 디지털 가상과 미디어의 홍수 속에서 회화의 힘은 쇠락하는 것 같았다. 정영주 작가는 이 가상의 세계에 빠지지 않았다. 오히려 손과 휴먼 터치, 정서의 힘을 믿어 의심치 않았다. 키케르 섬의 돼지로 변하는 선원의 모습은 자아 해체를 의미한다. 정영주의 자아는 언제나 명징(明澄)했다. 세이렌 섬의 노래의 유혹은 이성(理性)의 상실을 뜻했다. 정영주 작가는 광기로 치닫는 세태에서 끝까지 진실한 회화의 힘을 신뢰했다. 타인들이 광기(狂氣)와 센세이셔널리즘, 스펙터큘러리즘, 리모더니즘(re-modernism)으로 회화를 팔아넘겼을 때 작가는 소박한 포에틱(poetic) 순간의 정서를 회화에 담아야 한다고 믿었다. 그리고 고향으로 돌아와 반려자인 페넬로페(회화)를 구출했다. 서구의 모든 사조를 자기의 것으로 포장하지 않았거니와 들키고 싶지 않은 내밀한 이야기를 형식으로 승화시켰다. 초라해 보이는 집을 전면(全面)에 고르게 배치했으며, 근경에서 질료의 생생한 물질성이 두드러질수록 원경에서 불빛과 하늘은 영원한 공간성을 암시하여 회화의 복권에 힘을 불어넣었다. 한지 콜라주는 실재(實在)로서의 물질성을 극화시켰으며, 빛은 정서의 생동을 배가시켜 회화의 새로운 가능성을 예고했다.

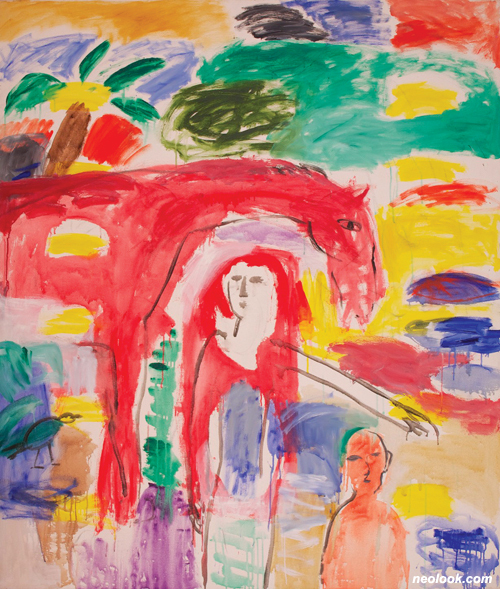

2. 정영주 회화에 내재한 두 개의 층위 ● 정영주 회화의 진가를 알기 위해서는 동서양 회화의 두 개의 신화에 대하여 이해해야만 한다. 하나의 이야기는 15세기 벨기에 앤트워프(Antwerp)에서 시작한다. 화가 캉탱 마시(Quentin Matsys, 1466-1530)는 원래 쇠붙이를 잘 다루는 대장장이였다. 캉탱 마시는 어느 날 한 화가의 딸과 사랑에 빠졌다. 대장장이는 화가를 찾아가 사랑하는 딸과의 결혼을 허락받고자 했다. 그러나 화가는 결코 대장장이와 같은 하찮은 지위의 사나이를 사위로 맞이하고 싶지 않았다. 어느 날, 캉탱 마시는 화가의 화실에 잠입하는 데 성공한다. 그리고 화가(장인어른)가 진행 중이었던 그림에 슬그머니 파리를 그렸다. 다음 날, 화가(장인어른)는 그림을 그리려다 무심결에 파리를 쫓아냈다. 몇 번을 휘둘러도 파리는 피하지 않았다. 화가(장인어른)는 파리가 그림인 줄 나중에야 알았다. 이 파리 그림을 누가 그렸는지 수소문했으며, 그 주인공이 대장장이(사위)라는 사실을 알았다. 캉탱 마시는 화가의 도제로 입문하는 것을 허락받았고, 마침내 화가의 딸과 결혼할 수 있었다. 그리고 캉탱 마시는, 우리가 아는 것처럼, 15세기 최고의 플랑드르파(派) 화가가 되었다. ● 또 하나의 이야기는 8세기 당나라 수도 장안(長安)에서 펼쳐진다. 동아시아의 전설의 화가 오도현(吳道玄, 680-740), 즉 오도자(吳道子)의 이야기이다. 오도자가 마지막으로 그렸다는 그림은 황제 현종(玄宗, 685-762)으로부터 의뢰받은 것이다. 현종은 당대 최고의 화가였던 오도자가 궁중의 벽화를 완성하길 바랐다. 오도자는 그림을 그리는 동안 황제 이외에는 아무도 그림을 볼 수 없도록 장막으로 가렸다. 황제는 그림 속의 아름다운 풍광을 보고 감탄했다. 그림 속에서 폭포가 소리를 내며 떨어지고 있었으며, 숲이 끝없이 이어졌다. 산은 치솟듯 높았으며, 구름은 광활한 하늘에서 뭉게뭉게 유영하고 있었다. 사람들은 비좁은 오솔길을 오르고 있었으며, 반대로 새들은 자유로움을 과시하며 날고 있었다. 그리고 산기슭에 동굴이 보였다. 오도자는 황제에게 말했다. "폐하, 보십시오. 동굴 속에 정령(精靈)이 머물고 있습니다." 오도자가 손뼉을 치니 동굴 입구가 열렸다. 이어서 "동굴 속은 빛이 가득합니다. 그 어떤 말로도 형언할 수가 없습니다. 제가 황제 폐하께 길을 안내해드리겠습니다." 오도자는 동굴 속으로 들어갔지만, 황제를 뒤로하고 입구는 닫혀버렸다. 황제는 놀라서 미동조차 할 수 없었다. 그림은 궁중 벽으로부터 사라졌다. 오도자의 붓 자국도 완전히 사라졌으며, 그로부터 오도자를 세상에서 본 사람은 없다고 한다.2) ● 캉탱 마시의 신화는 재현에 관한 것이다. 서구 회화사는 실재(實在)의 정확한 재현을 목표로 발전했다. 동아시아의 회화는 정확한 재현이 목표가 아니다. 그림에 들어가서 살며 느낄 수 있는 정서의 공유를 목표로 발전했다. 물리적 표면을 넘어서 화가가 세계를 바라보는 방법으로 인도하는 것이 그림의 도리였다. 동아시아의 화가들은 감상자에게 화가의 눈과 기량을 보여주는 것이 아니라, 감상자가 화가의 정신 속으로 진입하기를 원했다. 오도자에게 풍경은 물리적 공간이 아니라 내면적 공간이며 정신적 공간이다. 황제는 강토를 지배할 수 있을지언정 오도자의 정신을 지배할 수는 없다. 오로지 고귀한 정신으로써 하나 될 수 있는 회화의 강토만이 영원한 것이며 만대를 지나도 변치 않는 것이다. 우리는 힘으로 지배될 수 없는 정신적 강토를 가리켜 산수(山水)라고 부른다. ● 정영주 회화에 내재한 두 개의 층위는 바로 캉탱 마시와 오도자의 정신이다. 2008년부터 시작된 「도시풍경」 연작은 캉탱 마시의 정신으로부터 시작된다. 고층건물의 위용과 쇠락한 집의 초라한 물리적 표면을 대조적으로 보여주는 데 전력을 기울였다. 시간이 흐를수록 작가는 고층건물과 쇠락한 집 사이에서 드러나는 이분법적 존재론에서 벗어날 수 있었다. 우리가 어려서부터 만나고 느꼈던 골목과 골목으로 펼쳐졌던 만상(萬狀)과 그 형상에서 마음으로 기재되었던 만감(萬感)을 그리고 싶었다. 우리는 어렸을 때 골목으로 이어진 후미진 집에서 살았던 적이 있다. 어린 우리에게 그 골목과 산동네의 생활은 절대 비루하지 않았다. 어머니가 밥 짓는 냄새가 좋았고, 퇴근해서 돌아오는 아버지의 목소리가 정겨웠다. 옆집 친구의 목소리가 비단이불처럼 포근했다. 존재론적 안정(ontological rest)이 마치 이불처럼 모든 사물과 일들을 에워싸서 보호했다. 시간이 흐르면서 존재론적 안정은 존재적 시각(ontic view)으로 탈바꿈했다. 존재론적인 것과 존재적인 것은 천양(天壤)의 차이가 난다. 존재론은 시의 세계이며 존재적 세계는 과학의 세계이다. 전자는 정서의 충만을 최고의 가치로 여기며 후자는 정확한 계산을 목표로 삼는다. 모든 것을 계측적, 수량적 관점으로 본다. 따라서 인류사는 시적 시선(poetic view)으로 바라보는 가치에서 인과적 선후와 수단의 관점으로 세계를 재단하는 관점으로 이동한 역사이다. 이에 반해 정영주의 회화는 21세기인 지금 우리가 유년기에 총체적으로 체험했던 시적 시간(poetic time)을 완벽하게 극화시키고 있다. ● 작품 「Another World」는 시적 시간의 마력을 유감없이 발휘한다. 작품의 오른쪽 아래와 왼쪽 위에 산이 마을을 감싼다. 정영주 작가는 캔버스에 종이를 붙여 산의 형상을 완성한다. 그리고 캔버스 하단에 종이를 붙이고 오려서 집의 형상을 완성한 후 아크릴 물감을 수십 차례 올려서 집에 생명력을 불어넣는다. 종이와 종이는 서로를 뿌리 삼아 기대며 일어선다. 집과 집은 서로의 존재를 온기 삼아 생명력을 발산한다. 집과 집은 서로 의지해서 화면을 가득 채우며 끝없이 이어진다. 그리고 마치 연못에 돌을 던지면 동심원이 연못 가장자리 끝까지 퍼지듯이, 불빛은 동심원처럼 우리의 마음속까지 울려 퍼진다. 정영주 작가는 산과 집을 종이로 하나씩 붙이고 무수히 거듭되는 붓질의 퇴적 속에서 전체 풍경을 완성한 후 최종적으로 불빛을 살린다. 어렴풋한 분위기는 마침내 총체적 생기를 얻어 끝없이 생동하는 우주적 풍경을 연출한다. 정영주 회화 속 불빛은 풍경의 눈(the eye of the landscape)이다. 정신의 주재자(主宰者)이다. 우리는 그 불빛(눈)의 안내를 따라 마을 속을 거닐며 벽을 짚고 소리를 들으며 황혼이 지나 밤으로 진입하는 풍경의 냄새를 맡을 수 있다. 정영주 회화는 정확한 재현의 목표를 시작으로 내적 진리(시적 진리)라는 최종적 관문에 도달한다. 그리고 우리는 정영주의 작품 속에 진입하여 수량적, 계측적, 인과적 사유의 습관으로부터 마침내 해방된다.

3. 고향에 대한 두 관점 ● 동아시아 사회에서는 뿌리를 중시한다. 이를 지본의식(知本意識)이라 부른다. 모든 사물과 일에 대해서 본말(本末)을 따져서 판단한다. 사람에 대해서도 그에 대한 뿌리를 묻곤 한다. 그러므로 보학(譜學, genealogy)이 발달하게 되었다. 글씨에 관해서 서보(書譜)가 있고 그림에 화보(畵譜)가 형성되었다. ● 이에 반해 서구사회에서 뿌리를 중시하는 의식에 반발하는 사유가 동아시아 사회보다 발달하였다. 서구의 근대는 공동체보다 개인을 중시하는 방향으로 역사가 흘러왔기 때문이다. 빌렘 플루서(Vilém Flusser, 1920-1991)는 이를 '뿌리 없음(rootless)'이라 불렀다. 계보를 중시하는 인간의 의식은 식물의 형상으로부터 영향받았다는 것이다. 실제로 인간은 뿌리가 없고 유동하는 존재라는 것이 플루서의 설명이다. 정착하지 않고 자기결정으로써 자유를 획득해간다는 노마드(nomad) 개념은 디아스포라로서의 유대인 사회의 역사가 형성해낸 개념이다. 가령, 빌렘 플루서는 다음과 같이 말한다. ● 고향은 영원한 가치가 아니다. 특정 기술의 기능인 것이다. 여전히 고향을 잃고 고통을 겪는 이도 있다. 고통을 겪는 것은 고향에 달라붙어 있는 많은 유대 때문에 그런 것이다. 그 유대는 대부분 숨겨져 있고 의식으로 접근할 수 없다. 이와 같은 유대관계의 고착이 찢어지거나 분리될 때 개인은 고통을 경험한다. 마치 친지가 외과의의 집도를 받는 것과 같은 고통을 느낀다. 내가 프라하를 떠나게 되었을 때 우주 전체가 흔들리는 것처럼 느꼈다. 자아와 외부세계가 혼동되는 착각을 경험했다. 고통스러웠지만, 얼마 되지 않아 자유의 현기증과 도처에서 자유정신이라 부를만한 자유로움이 극심한 분리 증세를 극복하게 해주었다.3)

빌렘 플루서는 디아스포라로서 고향이 안겨주는 뿌리 깊은 유대관계보다 노마드의 자유정신을 중시하고 있다. 자유정신이란 공동체의 가치보다 개인의 가치를 인정해주는 사회분위기에 다름 아니다. 공동체의 가치란 인정(人情)과 베풂, 나눔, 공감을 중시하는 정서를 말한다. 또한, 아름다움, 취미, 도덕의지를 공감하고 서로에게 권장하는 사회 분위기이며, 이러한 공감을 존중하는 토대를 가리킨다. 이에 반해 개인의 특수한 시각이나 관점, 삶의 형식을 중시하는 태도를 자유정신이라 하며, 유동하며 격변하는 시대에 호응될 수 있는 정신이라 해서 개인의 가치를 중시했다. 이를 우리는 개인주의라고 배웠다. 개인주의는 산업사회 이후 고향을 떠나서 도회지로 몰려든 도시근로자와 도시근로자를 규제하는 지배계급이 공동으로 개발한 윤리이다. 따라서 20세기의 사상을 한마디로 정의하라면 산업사회 이전의 전통적 공동체 의식 지형과 산업사회 이후에 생긴 새로운 지형이 서로 충돌과 화해를 거듭하면서 그려낸 지형도라고 보아도 무방하다. 뿌리 있는 나무처럼 대대로 내려온 지형에서 생명력을 유지하느냐 아니면 뿌리 없는 유목의 가축처럼 신선한 풀을 향해 이동하느냐의 이미지로 사상의 지형도가 양분되었다. ● 서구에서 빌렘 플루서는 뿌리 없는 인간본질을 설파한 대표적 사상가인 반면에, 하이데거(Martin Heidegger, 1889-1976)는 고향을 숭상한 대표적 사상가이다. 하이데거는 과학기술이 지배하는 시대에 우리는 우리의 고유한 실존적 인간존재에 이르지 못하고 퇴락존재로 전락하게 된다고 말했다. 과학기술은 인간과 세계를 수량적으로 파악할 수 있을 뿐 존재론을 망각하기 때문이다. 이를 하이데거는 고향상실(Heimatlosigkeit)이라 규정했으며, 철학의 본래 과제는 진리가 훤히 드러나는 곳으로 귀향하려는 노력에 있으며, 예술 역시 망각된 진리를 다시 드러나게 해주는 매체적 현현이라고 정의했다. ● 현대미술 역시 고향의 개념에 상응하여 크게 두 기지로 구별할 수 있다. 하나는 공동체의 가치(고향, 대지)를 중시하는 미술이며, 또 하나는 공동체의 가치를 벗어나는 미술이다. 전자의 대표적 인물로 안젤름 키퍼(Anselm Kiefer, 1945-)가 있고, 후자의 대표로서 데미안 허스트((Damien Hirst, 1965-)를 손꼽을 수 있다. 전자의 심연에 반고흐(Vincent van Gogh, 1853-1890)와 밀레(Jean-François Millet, 1814-1875)가 자리한다면, 후자의 뇌리를 지배하는 것은 프란시스 베이컨(Francis Bacon, 1909-1992)일 것이다. 정영주 작가는 당연히 전자에 속한다. 그렇다고 안젤름 키퍼나 정영주가 완전히 고향을 회복했다고 말할 수는 없을 것이다. 어쩌면 넓은 의미에서의 모더니티를 추구하는 인간에게 고향상실은 필연적 사태일 것이기 때문이다. 우리는 현대라는 시점에서 도시라는 공간에서 살고 있다. 현대라는 시점과 도시, 더욱이 메트로폴리탄의 개념은 뿌리와 유대관계라는 정서 개념과 상궤를 달리한다. ● 현대와 도시는 노마드(nomad)와 관련되어 있다. 노마드는 그리스어 노모스(nomos)에서 유래되었다. 이는 경계지역(bounded area)이라는 뜻이다. 접미사 '–nomy'는 노모스에서 유래된 것이다. 따라서 천문학(astronomy)은 행성의 경계지역을 가리키며, 자율성(autonomy)은 개인의 자기결정의 경계지역을 뜻한다. 이에 반해 고향을 뜻하는 하이마트(heimat)는 고대 독일어 하이모티(heimōti)에서 유래되었으며 어떠한 상태나 조건을 뜻한다. 노마드는 물리적 경계를 뜻하는 반면, 하이마트는 심리적, 정신적 상태나 조건을 뜻한다. 고향을 그리워한다는 단어 노스탤지어(nostalgia)는 고향을 뜻하는 그리스어 노스토스(nostos)와 고통을 뜻하는 그리스어 알고스(algos)의 합성어이다. 역시 심리적, 정신적 상태와 연관되어 있다. 심리적이고 정신적인 유대를 영원히 그리워하는 것이야말로 우리의 숙명일 것이다. 진정으로 인간은 심리적, 정신적 상태와 조건으로부터 분리될 수 없다. 이것을 다시 회복하는 것이야말로 철학과 예술의 영원한 과제일 것이다. 정영주 작가는 영원히 끝날 수 없는 중대한 과제를 수행하는 세계에서 몇 안 되는 작가 중 한 사람이다. 정서의 회복과 회화의 복권을 위해서 오늘도 종이를 오리고 선과 면의 세계에 침잠하다 그 세계에 빛을 밝히고 있다. 나는 대지(Erde)와 세계(Welt)가 둘이 아니라고 믿지만, 때에 따라서 구분될 수 있다고 본다. 우리는 세계에서 살고 있지만, 우리의 본연은 대지에서 비롯된 것이다. 나는 대지를 어루만지는 작가를 사랑한다. 밀레가 그렇고 고흐가 그러하며 안젤름 키퍼와 정영주가 그렇다. ■ 이진명

* 각주1) "Philosophy is really nostalgia, the desire to be at home."2) Nathalie Trouberoy, "Landscape of the Soul: Ethics and Spirituality in Chinese Painting", India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 30, NO. 1(Summer 2003), pp. 5-19.3) Vilém Flusser, (trans.) Kenneth Kronenberg, The Freedom of the Migrant: Objection to Nationalism(Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003): p. 3.

종이 조각 하나하나를 붙여서 집을 만들고 마을을 이루며, 더 큰 세계를 만들듯이 과거의 추억을 머금고 있는 기억의 조각들이 모여서 지금의 "나"라는 세계를 만든다. ● 자고 일어나면 없어지고 어느새 또 생기곤 하는 빌딩들이 과연 나에게 어떤 추억을 만들어줄 수 있을지… 그곳엔 사람이 없다. 나도 없다. 허름한 판자집과 숨겨진 추억이 내일을 여는 등불이 되게하고 싶다. 나는 나의 작업을 통해 소외된 것들과 잊혀진 것들에게 그들이 즐길 수 있는 파라다이스를 만들어주고 싶다. ● 현재의 모습이면서 과거의 것처럼 보이기도 하는, 중의적 시간성이 또 다른 초현실적 분위기를 만들어낸다. 시간을 초월한 그 무엇은 나로 하여금 지금 내가 서있는 곳이 어디인지를 되돌아보게 한다. ● 한지는 빛을 흡수한다. 나를 기꺼이 받아줄 곳은 어디일까. 내 마음속 따뜻한 마을의 모습을 그리고 싶다. 내 작품을 보는 이들에게 지치고 힘들 때 돌아가면 언제든 문 열고 반겨주는 고향집 같은 편안함을 얻게 하고 싶다. ■ 정영주

1. The Another World Existing Inside the Banal World ● The poet Novalis (1772–1801) once said, "Philosophy is really nostalgia, the desire to be at home." In other words, philosophy is essentially homesickness; one's urge to build a hometown in every place one finds himself. And likewise, art is a product of the nostalgic urge. The hometown is so incredibly fertile with thought as a subject matter. One would be hard put to find a subject just as rich. This is because the hometown is the origin. As all men are born from dust and return to dust, every thought of the human being occurs during his journey of departing his hometown and returning to it. The desire to return to one's hometown is an irrefutable component of human nature, but fate is not favorable to every man, and there are situations where one is forced to leave his hometown and faced with the choice of letting it go. Odysseus in Homer's Odyssey belongs to the former case, and Abraham in the Bible the later. ● After the Trojan War, Odysseus tries to journey back to his hometown, Ithaca. However, in the process, he is forced to overcome numerous ordeals, including the seduction of the nymph Calypso who promises immortality, endless treasure, and limitless power; the battle against the man-devouring Cyclops Polyphemus; the lure of lotus, the narcotic plant, the isle of Circe where people are turned into swine, and the isle of Sirens whose intoxicating song led sailors to destruction. He finally makes it home, rescues his wife, and brings his family back together. In contrast, Abraham is someone who chooses to abandon his hometown, family, and loved ones solely by God's decree. The hometown can be the community that shields the individual from harm, and like a person's favorite comforter, it instantly provides a cozy environment one knows well. But Abraham follows God's call, parts with everything he has had, and heads to an unknown, dangerous land. While this act tells that one has absolute faith in God's will, it also represents one's willingness to take full responsibility for every result that occurs afterward. This is the solitude that Abraham faces. Leaving one's hometown is as painful as severing one's own flesh because the concept of hometown includes underpinning sentiments such as kindness, benevolence, sharing, and sympathy. ● Moreover, when God orders Abraham to sacrifice his only son, Isaac, his soul dives further from absolute solitude into the abyss of existence and arrives at absolute death. The moment one experiences absolute death is also the moment he accepts absolute nothingness, and yet, ironically, the acceptance of absolute nothingness is how eternal life begins. The true meaning of emptiness is to recognize that there is no such thing as the self. But, then, there is the other paradox of how emptiness is precisely that which conjures fullness. Specifically, the self and the rest of the world surpass the idea of valuation, such as loss and gain, and in turn, the world and I become one. This is how one is allowed to submerge in the state of completeness. ● Young-Ju Joung (1970–)'s artistic practice originates from experiencing absolute nothingness in the state of absolute solitude. Joung's universe has aspects of Abraham's paradox in how she had gained brimful completeness from absolute nothingness, but it also resembles Odysseus' journey because she left her home, came to understand the virtuous meanings of her hometown, and returned to it. This is why we sense Abraham's solitude in Joung's works and, at the same time, find Odysseus' bravery in them. ● Joung was born in Seoul in 1970, but she was raised in Busan, a southeast city in South Korea. She returned to Seoul for her undergraduate studies and majored in painting at Hongik University. Afterward, Joung left for France and studied in Versailles. Joung's works were well-received in the French art scene, and her artistic career took on a stable trajectory there, but she went to New York in 1997 and started her career anew. It was her long wish to have her works approved in the city that generates the newest trends in the international art scene. However, Joung was struck by a series of misfortune before she had yet settled into her new surroundings. By 1998, the Asian financial crisis had entirely devoured South Korea, and her personal life could not stay immune to it. Moreover, the constructivist-abstract painting style she was investigating at the time was yet to bear fruit. Regardless, Joung had to conclude her journey frequented by tribulations and return to her motherland. However, the return was not a true homecoming. Joung was yet to experience Abraham's absolute death, nor had she accomplished Odysseus' feat of rescuing Penelope. Although she had finished surveying the vast territory of paintings in the school of constructivism, abstract-expressionism, and the sublime, none of them had identified with her true self. In the life of an artist, the discovery of one's true self is the most critical event. For Odysseus, rescuing Penelope was the only thing that mattered in his universe, and for every artist, finding the form of practice and narrative unique to him is the absolute goal. Unfortunately, artists seldom achieve this objective. However, when the artist succeeds in establishing a self-identity, it guarantees him raison d'etre and foundational life. ● Ironically, self-identity comes from moments of crisis. A crisis drives the self to the extreme, and extremity allows one to distinguish who one is against others. Crisis, discrimination, criticism, criterion, and crimen are all words with the same origin, and their meanings are all based on the notion of differentiation. In the early 2000s, Joung went through a period where her life was demolished in every aspect. Her paintings had lost track, and she hardly had enough money to survive. Her acquaintances left her one by one, and all she had left was a feeble, powerless gaze. This was when Joung asked herself, "Why should I live?" ● The existential cause unfolds from the despairing inquiry of what good it is to live on, and at this moment, the I is discriminated from the banal others, and self-criticism advances to the fundamental question of "What am I?" To answer this ultimate question, the I must survey every possible criterion, but I am yet to know that I am committing an irreversible, life-threatening mistake by this very act because the I is not something that can be described by judging against external criteria. This I soon begins to criticize every other person except myself — a process that completely severs the I from every other. In a banal world, such actions and questioning are identified as crimen. But, in the another world; the art world, the same actions and questioning belong to the realm of sagas. ● In one of her days of world-ending despair, Joung was wandering through an urban center and ran into a bunch of small, run-down houses tucked amid a forest of skyscrapers. The weathered asbestos cement sheets, sagging ceramic roof, rusted front gate, walls run over with cracks, embankment gloomily sinking into itself, and concrete foundation covered in moss came into her eyes. Surrounded by sleek and impressive buildings, the collapsing houses looked much more inferior due to the contrast, and she easily identified herself with them. Also, she was used to seeing this kind of scene because it was common in Busan, where she grew up. Joung murmured to herself, "How could you be so exactly like me!" again and again. This was in 2008 and the beginning of the Cityscape series. The paintings juxtaposed the verticality of tall buildings that climb dignifiedly towards the sky with the horizontal imagery of crumbling houses that seem to lean onto each other just to stay up. The rising buildings represented the vivacity of the superstars — the individuals who lead the field they belong to — and the torn houses stood for her circumstance. The former also represented the narrative of art history, the story of maestros and masterpieces, whereas, in the latter, Joung seems to have prophesized the path her art would take. Gradually, Joung reduced the number of tall buildings in her paintings, and her scenery comprised solely of collapsing houses has pioneered a new style of landscape painting, the other-worldly painting. ● The life of the artist, or the life and sentiments of men in general, often take place in the course of departing the hometown and returning to it. Of the two models between Odysseus and Abraham, Joung opted for the latter and left her home. She studied in France and learned the Western schools' paintings and ideologies. And although the place she was trying to get to was close by, she took lengthy roundabouts to get there, where each step was painful, and finally made it back to her hometown. And the hometown told her the answer; that whatever one gains by lying about his roots always turns out to be vain. And Joung thought, "Whatever is the most familiar to me will always be the truth." ● Just as Abraham had followed God, Joung had put her faith in Western art and its schools and ideologies. And now, it was time for her to take responsibility for her belief, and she summoned courage and bade farewell to her God. And instead, she returned to her family and hometown, just as Odysseus had done. In Odyssey, Calypso promises Odysseus endless treasure and eternal life. To artists, the equivalent would be fame. But Joung repelled it, just as Odysseus had turned down the sorceress' offer. Polyphemus, the man-devouring Cyclops, represents one's pilgrimage through a period of savage, and albeit the dire perils her journey had presented, Joung has survived it. A nationwide catastrophe, multiple language barriers, information inequality, competition in the era of post-capitalism, globalism, and governance by diseased philosophy — she overcame all of these savages. The island of the lotophagi and the lotus plant, their main food and a narcotic, resemble how modern men indulge in the virtual world of technology. Facing the digital realm and the endless entertainment it provides, the influence of paintings seemed to have no choice but decline. But Joung did not bend to the trend; rather, it only strengthened her belief in the artist's hand, the human touch, and the power of the sentiments. The island of Circe, where people turn into swine, can be interpreted as one's soul experiencing a breakdown. But Joung's soul remained lucid throughout. The seduction of Sirens and their song represents situations where one's intellect is lost, but even when the world around her was escalating towards insanity, Joung never yielded and continued to believe in the power of sincere painting. While numerous others were selling paintings under the label of mania, sensationalism, spectacularism, and re-modernism, Joung remained firm in her belief that paintings must capture the modest sentiments of poetic moments. And she came back to her hometown and rescued painting — her Penelope and spouse. She did not pretend her work to be the compendium of all Western schools and instead amplified her private, cherished narrative into a formative style. In her paintings, she began to place run-down houses in the foreground in an even layout. In the close-up view, Joung accentuates the houses using the conspicuous materiality of her mediums, but in contrast, the view afar shows the lights and the sky fading out into an infinite atmosphere, the empowering imagery that foreshadows the return of paintings in our era. Her mulberry paper collage technique dramatizes the houses' existential manifestation via materiality, and her use of light catalyzes the motility of the sentiments, presenting a new potential in painterly practice.

2. The Two Layers Inborn in Joung's Paintings ● To understand the true value of Joung's paintings, one must first learn about two myths in East Asian and Western painting traditions. One takes place in 15th century Antwerp, Belgium. Painter Quentin Matsys (1466–1530) was originally a highly-skilled metalsmith. He fell in love with the daughter of a renowned painter. Matsys met the painter and asked him for his daughter's hand. But the painter in question did not want a metalsmith, a low-class man, to become a part of his family. One day, Matsys broke into the painter's studio without being noticed and painted a fly on the painting the painter was working on. The next day, the painter returned to his studio, naturally noticed the fly, and waved at it to drive it away. But the fly did not budge. After several such attempts, the painter realized that the fly was a painting, not a real insect. He gave orders to find who had painted the fly and found out that it was the metalsmith who had proposed to his daughter earlier. He proceeded to accept Matsys as his studio apprentice, and eventually, Matsys married his daughter. And the rest is well-known to us — Matsys went on to become one of the best Flemish painters of the 15th century. ● The other story takes place in 8th century Chang'an, the capital of the Tang Empire, a tale of Wu Daoxuan (680–740), also known as Wu Daozi, a legendary painter in East Asia. The last painting Wu painted in his life is known to be a commission from the Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685-762). At the time, Wu was reputed to be the best painter of his generation, and Emperor Xuanzong wanted him to paint a mural in his palace. While working on the mural, Wu always kept it covered under a veil so that no one else could see it but the emperor. When Wu revealed his painting, the emperor caught his breath at the unbelievable landscape unfolding before him. Water was falling from a giant fall making loud noises, the forest was fading endlessly into the horizon, the mountains were rising so high as if they were to touch the heavens, and the clouds were gently sailing through the sky. There were people climbing narrow uphill paths, and contrastingly, the birds were flying at such liberty as if they were boasting of their freedom. And, at the foot of one mountain was the entrance of a cave. Wu said to the emperor, "My majesty, please look. That cave is inhabited by auspicious spirits." Wu clapped his hands, and the cave's entrance opened. He continued, "The cave flows with light. The beauty is impossible for me to put in words. Please, let me guide my majesty on a tour of the cave." Wu walked into the cave, but the entrance immediately closed behind him, leaving the emperor by himself. The emperor stood frozen from the surprise. Then the painting disappeared from the wall. Every brushmark Wu had painted vanished without a trace; that was the last time he was seen.1) ● The theme of the Matsys' tale is representation. On the same vein, the history of Western painting is the pursuit of an exact representation of reality. On the contrary, East Asian painting did not aim for representation. Instead, it aspired to recreate sentiments and made paintings that could deliver and share the feelings the artist had felt; in other words, making viewers feel what might it be to live inside the painting. It was the artist's duty to guide the viewer beyond the physical surface of the painting and show him how the artist viewed and felt the world. In other words, painting in East Asia was not about presenting technique and skills of observation; it was about the artist wanting his viewers to see and feel the world in the way he saw and felt it. Likewise, to Wu, a landscape painting was not about physical space but the inner and the psychological realm. The emperor may move mountains and bend rivers, but he cannot take command of Wu's spirit. The only immortal landscape is the land and water captured in a painting — fused into a single entity by the artist's venerable spirit — which remains unchanged through thousands of generations. This tradition is known as shanshui (山水, mountain and water), a genre of landscape painting featuring the mental imagery of land and water, one that cannot be dominated by brute force. ● Joung's paintings have two inborn layers: the spirit of Matsys and Wu. Her Cityscape series, initiated in 2008, had begun from Matsys' spirit. The earlier paintings concentrated on recreating the physical surfaces of weathered, crumbling houses and contrasting them with the majesty of tall buildings. But as more time passed, she was able to move away from the binary ontology of skyscrapers and run-down houses. She simply wanted to paint the alleys that were the backdrop of childhood for the vast majority of South Korea's older generation, paint the numberless facets they have had, and the countless feelings they had generated. Most people in this generation, including myself, can recall living in such a run-down house tucked inside a maze of alleys. But when we were youngsters, our life in the alleys never felt like poverty. We remember our moms by the fragrance of the rice-cooking steam, our dads by the voice of their greetings coming home from work, and the conversations with our friends next door were as soft as silk bedding. A state of ontological rest covered us like a cozy comforter and shielded everything and every being from harm. Over time, the ontological rest transformed itself into the ontic view. The ontological and the ontic are as different as night and day. The ontological belongs to the realm of poetry, but the ontic belongs to the realm of science. The former considers the fulfillment of sentiments as the absolute purpose. The latter prioritizes precise calculation and observes everything from the viewpoints of measurement and quantification. In other words, the history of mankind is the story of shifting from the values of the poetic view to the perspective of measuring the world by causal order and means. However, Joung's paintings immaculately theatricize the poetic time that we, the older generation of South Koreans, share as a collective in the context of the 21st century. ● The painting Another World flaunts the magical power of poetic time. The painting features a town embosomed by mountains from the upper left and the bottom right. Joung created the shape of the mountains by pasting sheets of paper; likewise, she formed the houses by pasting and cutting paper. Afterward, she painted her shapes with several dozen layers of acrylic paint, which brought the houses to life. One sheet of paper leans on the other, becomes roots for each other, and raises itself. The houses provide each other the warmth rising from their existence and radiate the liveliness of life. And the houses, leaning on each other and providing support for other houses, fill the entire canvas and fade forever to the horizon. Just as how a stone tossed into a pond sends out concentric ripples that reach every edge of the pond, the light flowing out from Joung's houses sounds concentric circles that reach the deepmost of our hearts. Joung creates her mountains and houses by building many layers of paper, sculpts the overall landscape with the accumulation of her countless, tireless brushstrokes, and finally, retouches the lights at the end. The vague ambiance then gains a collective life, and the painting unveils the view of a universe that pulsates eternally. The lights in Joung's paintings are the eyes of the landscape, the master of the human soul. The lights (the eyes) allow us to wander into the town's alleys, hold onto its walls, listen to its sounds, and smell the scent of the land progressing from dusk to night. Joung's paintings begin by aiming for an accurate representation, but they always end by reaching the final gate of inner truth (poetic truth). And by entering them, we are, at last, released from our habits of measurement, quantification, and causal reasoning.

3. The Two Viewpoints on Hometown ● By tradition, East Asian societies have greatly emphasized one's roots; the theory of knowing the root (知本意識; Ji-Bon-Ui-Sik), for instance, understood every object and event by investigating their root and outcome. The same principle was applied in understanding an individual, so tracking one's root, or genealogy, was meticulously developed. Calligraphy was understood via studying the genealogy of calligraphy (書譜; Seo-Bo), and painting was understood via the genealogy of painting (畵譜; Hwa-Bo). ● In the Western world, the aversion to emphasis on roots was much stronger than in East Asia because the modern history of the West had consistently put the individual above the community. Vilém Flusser (1920-1991) identified this as rootlessness. He believed that humans had developed the idea of genealogy by taking inspiration from the anatomy of plants. Flusser points out that, factually, humans are mobile beings and have no roots. In contrast, the concept of the nomad — obtaining continual freedom by making sovereign choices and not settling in one place — was developed by the Jewish people, who have retained their culture as a historic diaspora. For instance, Flusser has written, ● Homeland is not an eternal value but rather a function of a specific technology; still, whoever loses it suffers. This is because we are attached to heimat by many bonds, most of which are hidden and not accessible to consciousness. Whenever these attachments tear or are torn asunder, the individual experiences this painfully, almost as a surgical invasion of his most intimate person. When I was forced to leave Prague (or got up the courage to flee), I felt that the universe was crumbling. I fell into the error of confusing my private self with the outside world. It was only after I realized, painfully, that these now severed attachments had bound me that I was overcome by that strange dizziness of liberation and freedom which everywhere characterizes the free spirit.... The transformation of the question "Free from what?" to "Free for what?"—an inversion that is characteristic of freedom gained—has since accompanied me like a basso continuo on my migrations. All we nomads who have emerged from it share in the collapse of settledness.2) ● Flusser finds more importance in the nomad's spirit of freedom than the deeply-rooted communal ties that the hometown provides as a diaspora. The spirit of freedom, however, is not a complicated concept. It merely indicates a society that accepts the values of the individual just as much as the values of the community; specifically, the social agreement that prioritizes kindness, benevolence, sharing, and sympathy, the sharing and recommendation of aesthetics, hobbies, and ethicality, and the social foundation that respects such spirit of commonness. In contrast, the spirit of freedom is the attitude that prioritizes each individual's unique view, values, and way of life. The ideology saw great importance in an individual's values because it believed that such acceptance would allow societies to be adaptable in fluid, rapidly-changing worlds. This school of thought was taught to us as individualism, the ethical system co-developed by urban laborers who had left their hometowns and moved to cities following the industrial revolution, and the capitalist class that supervised the laborers. Thus, in essence, the philosophical developments of the 20th century could be abridged as the topography created by the numerous collisions and reconciliations between the traditional philosophy of communal values and the new schools of thought born after the industrial revolution. The geography of epistemology now had two halves: the ideas of building a life on inherited land, like how a tree grows on its roots, and the imagery of rootless nomads who are always on the move to find new pastures for their cattle. ● Of Western philosophers, Flusser was the main proclaimant of human nature's rootlessness, and in contrast, Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) was the stand-out advocate of the hometown. Heidegger said that, in an era dominated by science and technology, human beings cannot reach authentic human existence and are instead downgraded to decayed existences because their means are limited to quantitative measurements of men and the universe and have no capacity for remembering existentialism. Heidegger identified this state as homelessness (heimatlosigkeit) and said that philosophy's true goal is in the endeavor to return home — where true knowledge is revealed to us coherently — and art the materialistic incarnation that helps us see the truth we have forgotten. ● Contemporary art can also be identified into two branches through the concept of hometown. One is the art that prioritizes the values of the community (hometown or earth), and the other is the art that attempts to escape from these values. Anselm Kiefer (1945–) is the illustrative case of the former, and Damien Hirst (1965–) embodies the latter. Kiefer's unconsciousness could be seen to accommodate Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) and Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), whereas Hirst is doubtlessly enthralled by Francis Bacon (1909–1992). Joung, of course, belongs to the former. However, it would not be fair for us to believe that either Kiefer or Joung have fully recuperated the hometown because, in the broader picture, homelessness is likely a predestiny for all men pursuing modernity. In our modern era, a large chunk of the population lives in cities. The modern times, the city, and especially the metropolitan, are the polar opposite of sentimental concepts such as roots and bonds. ● Modernity and the city are both related to the concept of the nomad. The word nomad originates from the Greek word nomos, which means "the boundaries of an area." The suffix -nomy also derives from the word, whereby astronomy is the study of a planet's boundaries, and autonomy is the boundary of an individual's power of decision. On the other hand, the word heimat derives from the Ancient German word heimōti, meaning "a state or condition." Nomad indicates physical boundaries, whereas heimat concerns psychological and inner state and conditions. Lastly, nostalgia is a compound of two Greek words, nostos and algos, each meaning "hometown" and "pain." Once again, the word describes a psychological, inner state. It is our fate to forever yearn for our psychological and inner bonds. It has been shown that humans can never be entirely severed from psychological, inner states and conditions. And recuperating them will forever remain the mission of philosophy and art. Joung is one of the few artists in the world undertaking the absolute, eternal project. To recuperate sentiments and reinstate painting, she spends each day cutting papers into shapes, exploring the realm of points and lines, and, at last, bringing light into the realm. I have always believed that the earth (erde) and the world (welt) are inseparable, but at times, they may be distinguished when necessary; for instance, the world is what we live in, but the earth is where we come from. I have always loved artists who caress the earth. Earlier, there were Millet and Van Gogh, and now we have Kiefer and Joung. ■ Jinmyung Lee

* footnote1) Nathalie Trouberoy, "Landscape of the Soul: Ethics and Spirituality in Chinese Painting", India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 30, NO. 1(Summer 2003), pp. 5-19.2) Vilém Flusser, (trans.) Kenneth Kronenberg, The Freedom of the Migrant: Objection to Nationalism(Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003): p. 3.

Houses and villages are created by placing the pieces of paper, Like creating a bigger world, the pieces that embrace memories of the past gather to create a world of "myself" today. ● The buildings appear and disappear when I fall to sleep and wake up every day. I wonder what kind of memories these buildings will grant me... There are no people. I also don't exist. I hope shabby shanties and concealed memories become the lights that open our tomorrows. I wish to create a paradise for the objects that have been neglected and forgotten through my artistic practice. ● The picture screen creates a supernatural atmosphere throughout an ambiguous temporality, which seems like a past and present. 'Something' beyond time makes me to look around and reflect where I am currently standing. ● Paper embraces the light. Where would a place accept me. I want to paint a warm village that exists in my heart. Through the artworks, I want to make the viewers feel comfort like the moment when we open the doors of our sweet homes and when our families welcome us. ■ JOUNG Young-Ju

Vol.20220727c | 정영주展 / JOUNGYOUNGJU / 鄭英胄 / painting

'인사동 정보 > 인사동 전시가이드' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 정효웅展 '허실의 경계' (0) | 2022.08.04 |

|---|---|

| 인사동,북촌,서촌,광화문,평창동지역 갤러리, 2022년 8월 전시일정 (0) | 2022.08.01 |

| 고권展 '너의 이야기 Your story' (0) | 2022.07.30 |

| 김은정_박광수_이우성_장재민_지근욱_허수영展 '살갗들' (0) | 2022.07.27 |

| 필립 그뢰징어展 'WHY SO SERIOUS?' (0) | 2022.07.25 |